- Home

- Morgana Gallaway

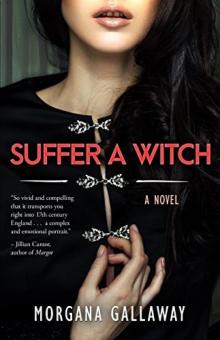

Suffer a Witch

Suffer a Witch Read online

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

ST. BRIDE’S PRESS

© 2011 by Morgana Gallaway

Digital Edition

Print ISBN: 978-0-9836989-0-6

Digital ISBN: 978-0-9836989-1-3

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Cover image credit Maksim Toome/Shutterstock.com

1. Fiction 2. Historical Fiction 3. Witch Trials 4. Witch Fiction

CHAPTERS

Chapter 1: The Thorn Inn

Chapter 2: The Green Man

Chapter 3: The Cunning-Folk

Chapter 4: The Dark Places

Chapter 5: The Speaking Raven

Chapter 6: The Fevered Land

Chapter 7: The Meeting of the Roads

Chapter 8: The Discovery

Chapter 9: The Watchers

Chapter 10: The Turning of the Worm

Chapter 11: The Gaol

Chapter 12: The Dissolving World

Chapter 13: The Pigeon in the Rafters

Chapter 14: The Last Dance

Chapter 15: The Skull in the Hollow

Chapter 16: The Pond at Mistley

Epilogue

Historical Note

Research Acknowledgments

For Sybil, who was waiting

for me at the end of it

He began as usual. He used a silk rope because its softness reminded him of her skin, and its knots were like her calluses. It was midnight on a Friday and he knew what that meant. It was the hour of the black mass. It was the hour he was in their grip.

He tied the rope around the bedpost, while the other end was slipped into a simple noose. He put his head through it, already excited, heart pumping his black sinner’s blood. He fell to his bare knees on the floor next to the bed, the supplicant’s position, and the ligature tightened around his throat.

Into his own fervent darkness he fell, sweating, straining, crying.

In the last moments, as everything went coil-tight and starry-eyed, he heard the whispers, as he always did.

“Dance-y, dance-y.”

Her silken hands were relentless.

“Master, faster, vow at-laster.”

He was a sin-born little boy.

“To you I say, I am a witch.”

“I meet with him in the night —”

“—the night.”

“I lay with him in the night.”

“Meet me, circle plea, round and round and round we go! Witch, dee, scree, scry, scratch!”

They screamed and cackled and then he collapsed, exhausted from the fight. He barely had the strength to reach up and untie the knot, to free himself. He crawled into his cold bed with a murmured prayer, trying to remove the flush of shame, the knowledge of his unclean beginnings. “I am of God’s flock, and God hates you,” he whispered back to the fading voices.

Sleep came.

After hours of vague and threatening dreams, he swung his feet over the side of his down-stuffed mattress and hit the wood floor with a thud. He always got up on the right side of the bed. The left side of things was sinistra.

Above all else, Matthew Hopkins made sure to wake up the godly way.

He broke the thin cover of ice in the washbowl and splashed once over his face. It did little to dispel the sheen of his skin, oily from sleep. He stared at his reflection in the gloom, reminding himself there was nothing enchanted, nothing unusual about his face this morning: dark eyes, pointed nose, solid cheeks, a trimmed beard on his chin, brown hair with a few streaks of lighter ash. No warts or boils.

Hopkins reached over and pulled back the curtain, eager to see the light of day. Below him was the high street of Mistley, Essex. Roofs competed for space and beyond them was a stretch of watery fenland and woods. They were close to the sea here. Ships sailed up the estuary of the River Stour for trade and transport, but despite this the town had a grim, provincial feel. Its people did not trust foreigners much these days. In times of violence it was best to keep to one’s loyal neighbors.

England was in the midst of a civil war, and this was the heart of pro-Parliament country, reformist men and women who’d had enough of the decadence of kings and aristocrats and Catholics. Hopkins counted himself as one of the free thinkers who yearned for a simple, strict, pious life.

At the foot of his bed, his dog stirred, always waking up with her master. Her name was Elspeth, a fine greyhound, but marred with a fight scar on her left ear. She’d come to Hopkins as a pup two years ago. He petted her on the head and then pulled on his shirt, breeches, and his doublet jacket, doing up the tiny buttons in a straight line all the way to his throat. He brushed his cuffs into place, adjusted his collar, and made sure his white shirt was visible through the slashes in the doublet’s fashionable sleeves. Right foot first, he pulled on his boots, polished black leather turned down in a bucket top style.

Peering out the window once more and seeing the barest layer of icy dew on the ledge, he decided in favor of his short cape of black wool. Satisfied, he was dressed and ready for the day.

He didn’t stay in the best room at the Thorn Inn—that was reserved for visiting dignitaries or rich men—but it was the second-best, because Hopkins owned the place. He’d bought it two years ago after coming into an inheritance, and in that sense Elspeth and the inn were tied together in his life. He owned another house as well, a small but well-kept cottage down the street.

The kitchen downstairs was cold and empty. He took a moment to shout at the old cook who was just hanging her cloak, late and full of excuses. He told her that constant hard work was a Christian duty and she had better get busy.

Irritated, he caught a tin mug from the shelf and dipped it into the water bucket. The cool taste reminded him of baptism, and of the purity required of God’s servants. He wondered if his father was looking down from his place in Heaven, waiting for his youngest, most problematic son to prove himself.

Hopkins sat down on a bench and leaned his elbows on the oak table. A sigh of ennui overtook him. Twenty-four years old, and he owned this inn, but that could not be all there was to life. Faith, he told himself, have faith. Rather than following his brothers to Cambridge, he’d hesitated, and fumbled around, and ended up being sacked from the one position he’d managed to procure.

It had been a legal clerkship in the city of Ipswich that had lasted but a few disappointing months. He’d worked for a lawyer who said his skill with letters was fine, but that he was stubborn and self-righteous, and that his sermonizing drove away clients—criticisms that stung to this day. Swallowing, he pushed the memory back into one of the dusty cracks of his mind. Faith.

The wooden door creaked on its hinges and an old man entered. With him he brought the first drops of rain from an iron sky.

“Sir Grimston,” said Hopkins, stepping forward and bowing. “Greetings.”

Sir Harbottle Grimston was the kind of man for whom the best room would be reserved. He was a landowner and a Member of Parliament, and he’d taken a mentor role with Hopkins. “Nasty weather,” Grimston said, shaking off his fine wool coat. He had a beefy constitution which made him seem younger than his seventy-some years. He also never hesitated to denounce the evils of the world, which he did when he learned there was no breakfast to be had.

“I have already admonished the cook,” said Hopkins, nerv

ous of being ill-judged.

“Hmmph,” said Grimston. “Sit, my friend. There’s been an incident at Lawford. Something wicked is afoot.”

A tiny thrill ran through Hopkins. He knew well the voices on his Friday nights. “Good sir, tell me.”

Grimston sat down and hoisted his foot onto a stool. “The gout is returning,” he grumped.

Hopkins tried to wait with patience.

While Grimston re-adjusted his posture and the tie around his neck, and ordered the cook to fry eggs, Hopkins could wait no longer. “Please, sir. What incident in Lawford?”

Grimston pursed his lips. “A goodwife, who was with child, collapsed during the church service. She then birthed a stillborn babe … I’m loathe to say it … but the babe was deformed. It was witchcraft, no doubt.”

Hopkins leaned in closer. Witchcraft. A vision of blazing pyres and cloven feet quivered in his mind’s eye. He had met witches before. “Who has done this against an honest man’s wife?”

“There have been many years of troubles in Lawford,” said Grimston. “Murders, unexplained illness … and of course last year, the good Richard Edwards was cursed! He lost several livestock and then his own son fell dead in a fit.”

Hopkins remembered. If witches had the nerve to curse an established gentleman, what was next?

Grimston continued. “There are repeat offenders,” he said. “Like old Elizabeth Clarke, that beggar and widow of a scoundrel. Once, she made the sign of the evil eye at me when I refused to give her coinage.” He shuddered. “With this war on, we cannot find justice in the courts. No one in London cares about witchcraft afflicting us here. ’Tis our duty to maintain the rule of law ourselves. Hopkins, with your background in jurisprudence, I would have your help in this matter.”

Enthralled with the idea of prosecuting witches, Hopkins nodded, perhaps too fast. “I am your servant.”

“What do you know of laws and techniques? I must have experts here, mind you. The matter is too grave for amateurs.”

Hopkins was no amateur. He believed in knowing one’s enemy and was better-read on the subject of witchcraft than anyone he knew. “But of course,” he said. “I have made a study of the laws and procedures of witchcraft trials.”

At Grimston’s impressed nod, Hopkins told his mentor how witches’ lies might be unraveled by depriving them of food and rest for several days. Godly women could endure such hardships, while witches would confess. Hopkins lowered his voice, arriving at the most interesting tests. “Physical proofs include unnatural marks, protrusions, and teats on the body—evidence of the imps that suckle their blood for nourishment. Test them by pricking with a needle or a sharpened bodkin. If it does not bleed, it is proof.” Hopkins licked his lips. “Often these witch’s teats are found near her privy parts, for demonic copulation is part of the pact.” An image flickered through his mind of a woman with a red-eyed animal suckling between her legs. It caused an uncomfortable rush of blood through his body.

Grimston was likewise appalled and shifted in his seat. “Indeed, a pious woman would have no cause for the unusual on her body, which is created by God.”

“And there is the way advocated by King James, which is the swimming. If she floats, she is light on morals indeed, and rejects her baptism.”

Grimston slapped his knee. “I’m convinced, my boy. There is none better than you to help me.” He stood up. “Ride with me to Manningtree later this week. There is someone you must meet, another godly man who is willing to be a witch-finder. I shall introduce you.”

After Sir Harbottle Grimston had eaten his breakfast and taken his leave, Hopkins’s heart fluttered in his chest. This could be his calling. His cure.

He quit the Thorn Inn for his nearby cottage and flung open the door, taking two long strides to the bookshelf. He pulled a favorite out of its place. Penned by King James I himself, it was a guide to the work of the Devil in England: Daemonologie, it was called, and within it was the key to hunting witches. He could smell his destiny in the book’s instruction.

He sank into a chair and sighed relief. There was an explanation for his suffering. On Fridays—according to his texts, the day of the witches’ unholy sabbat, their orgy with demons, the day of their malefic workings—he had heard their whispers. The strange urges that passed through his mind, the nameless deeds that he was compelled to perform … this report of witchcraft meant there was nothing wrong with him. It wasn’t his fault. No, it meant he had a gift for detecting witches.

His fingers brushed the rough edges of Daemonologie. The book told of something called the Devil’s Register, a list of all the witches in Christendom. When they became witches, they signed the list, giving their souls over to Satan.

He knew of at least one woman whose name was on that Register. Long to Hell she may have been, but her sisters still haunted him.

If he discovered something so evil, and brought it into the waiting arms of justice, perhaps he could begin to pay off the debt on his soul, inflicted by the weight of his unlawful parentage. Perhaps the urges would stop. Father, I will prove I am your son, equal to the others, he prayed … not to the Lord, but to his dead human father.

He coughed. He would attend church. Then he would be ready.

THREE GIRLS SPIRITED THROUGH a wood at dawn. Their pace down this familiar pathway was sometimes leisurely, meandering; other days, like today, it was with strong purpose. This was in part because of the morning chill. It was the beginning of February, in the Christian year of 1645, and the ground was frozen from a long winter. The thaw, the girls hoped, would begin soon.

There was no color to be found amongst the bare branches and frosted floor. The girls’ dresses and cloaks were dark, plain wool, although one of them had a delicate white lace collar. Their hoods were pulled tightly over their linen head caps. Sturdy shoes protected their feet. They did not speak until deep in the forest, because even at this early morning hour, someone might overhear them.

“Almost there,” said Philippa, known to her friends as Pippa. Her hazel eyes seemed to kindle with excitement. Her grin was wide and unrestrained.

Sybil, whose blond hair escaped in wisps from under her cap, giggled. She skipped through the trees rather than walked, always a little off the path from the others.

Alice, the third, gave a bashful smile to Pippa, blinked with gentle brown eyes, and clutched a small clay jug close to her chest.

Past a brook, around the trunk of a wizened warty oak, and through a cluster of boulders, they reached their destination: a small grove of apple trees with a slight depression in the center. Here the ground was charred from fires previous. “We must call the spring,” said Pippa. This outing had been her idea.

“Ash Wednesday today and the feast of St. Bride, for the unreformed,” said Sybil, her voice angelic like her pale gold hair.

“Maybe this year we shall be brides,” said Alice.

“Not if we don’t light the fire.” Pippa produced a small sachet from under her winter cloak. “This be all we need, if Alice brought the milk.”

Alice nodded and held up the clay jug. “I had to milk the cow meself,” she said.

Sybil shuddered. She was afraid of cows.

“’Twasn’t terrible,” said Alice. “But I feared it would make a noise. Me father will wonder who done Daisy so early today.”

Pippa winked. “We need twigs. Oh, Sybil, you’ve already started!”

Sybil had wandered off into the trees, bending every so often to choose a thin stick of fallen wood. She hummed to herself, a song on the chilly wind. The other two followed. Pippa stripped off her mittens and chose the best and driest pieces to begin their fire. Glancing up at the sky, she saw heavy clouds closing in, and nodded her head in satisfaction. Tradition held that bad weather now would mean an early spring.

Firewood gathered, the girls built a pyramid of sticks on their usual spot. Always the fire-starter, Pippa struck a flint, and a bright spark danced and caught on the dry moss inside. A tender lick o

f flame took hold of a piece of kindling. From there it spread, growing in strength, until it was time to place larger pieces on top. The golden glow was like a splash of sunshine in the grey forest. The girls smiled at their accomplishment.

Pippa then brought out a handful of herbs from her sachet, preserved over the winter: dried primrose and poppy seeds. “All of us,” she directed, holding out pinches for the girls to take. They tossed them into the fire and watched as they were consumed, crackling.

Alice uncorked the jug of milk. “Ready,” she said.

They joined hands and walked around the fire in a deosil circle, the same direction as the hands of a clock. Pippa began to chant a made-up rhyme. “Men, sin, kin, din, win. Baby, lady, baby, fate-y.” The others joined, singing.

“Milk for the earth,” Alice said, and tipped the jug forward. A white, foamy stream fell to the ground, following the circle they carved with their feet. Tiny wisps of steam came off the milk, still lukewarm from the cow.

“Take our offering, Lady of the Forest,” said Pippa. “Great Lady, fair Maiden, we implore you. Send us husbands this year!”

Alice glanced upward. “Lady Mary, mother of Jesus, hear us.”

“Winter goes to sleep,” sang Sybil. “Spring, ring, thing, wing.”

They danced their circle. Pippa laughed and threw her linen cap to the ground, releasing a tumbled mass of wavy dark hair. Faster and faster they circled the fire until they were dizzy, laughing, and gasping with breath fogging around them.

“Look into the fire,” Sybil pointed, “and see their faces!”

“Whose?” asked Alice.

“Our husbands,” said Sybil with a firm nod. Her pale eyes lost their focus as she stared. Sybil saw things that others did not.

“What do you see?” Pippa giggled.

“A dark man,” said Sybil.

Pippa raised an eyebrow. Their neighbor Thomas Radcliff had dark hair, but he was away.

A tiny crease appeared between Sybil’s eyes. “He has a hat, and a cape, and boots,” she said. “He has a dog? He looks … oh, I’ve lost it.” A breathless laugh escaped her.

Suffer a Witch

Suffer a Witch